Feinberg, Stanley Knox

Stanley Knox Feinberg, age 90, prominent Chicago attorney , beloved husband for 63 years of the late Lois, nee Simon; devoted son of the late Anne and Judge Michael Feinberg; loving brother of Eileen (Bernard) Burdman and the late Betty (late George) Epstein; adored uncle of Michael (LaDina) Epstein, Barbara (Richard) MacArthur, Nancy Katz and the late Alan (Bebe) Epstein; proud great-uncle of Mark (Karen), Jay (Julie), Craig (Joy), Ryan and Julie Epstein, Jessica and Aaron Katz, Jeffery Gill, Timothy and Adam MacArthur; and greatgreat-uncle of five. Private Cryptside service Wednesday. Contributions may be made to Friedman Place, 5527 N. Maplewood, Chicago, IL 60625. Info, The Goldman Funeral Group, 847-478-1600.

Charlotte’s Crime of the Century

When gangsters hit a mail truck on the Queen City’s peaceful

streets, they had no idea whose territory they had invaded.

It didn’t take a genius to figure out what had happened.

Only days earlier, a tip came into the police department that something big was

about to go down in Charlotte.

As Frank Littlejohn surveyed the scene and listened to

eyewitnesses, the chief of detectives knew this was the something big.

The mail truck was heading away from the railroad depot on

Third Street when a car darted out of an alley and slammed on brakes in front

of it. In swift, sure movements, four men, at least one brandishing a machine

gun, jumped out of the car and swarmed the truck.

The gunman shoved the tommy gun into the truck’s cab and

disarmed the driver. At the same time, two men walked to the back, cleanly

clipped the lock on the rear doors with a pair of wire cutters, forced the mail

clerk out of the truck, and grabbed several sacks.

In less than two minutes, the thieves, loot in hand,

retreated to their car, and, in a cloud of dust, they — and more than $100,000

in cash and bank notes — were gone.

Mob hit

Littlejohn had no doubt that this crime, well executed and

committed in broad daylight on a clear morning, was a mob hit. He was right.

The year was 1933. The day, November 15. In Chicago,

Illinois, Al Capone was battling Roger “The Terrible” Touhy for control of

illegal beer and liquor sales in that city’s northwest suburbs. Five months

earlier, Capone’s agents framed Touhy for the kidnapping of Jake Factor, a

known gangster (and brother of the famed makeup artist Max Factor). Touhy was

awaiting trial when four of his henchmen headed south to “raise” money for his

defense.

Charlotte in the 1930s had few if any connections to

organized crime. Cotton fields surrounded it, and textile mills filled it. As

in many towns at the height of Prohibition, staunching the flow of bootleg

liquor was one of law enforcement’s primary occupations. But Charlotte, already

with a population of roughly 80,000, was on its way to becoming a financial

center.

“There were multiple skyscrapers and fancy department stores

and the new offices of the Federal Reserve, which opened in 1927,” says Dr. Tom

Hanchett, staff historian at the Levine Museum of the New South. “Money flowed

in and out of Charlotte.”

Touhy’s men probably thought targeting deposits on their way

to the Federal Reserve in the so-called sleepy South seemed like an easy mark.

They were wrong.

‘Finest detective in America’

What Touhy didn’t know was that he had sent his men to

commit a headline crime in a city patrolled by a man who J. Edgar Hoover would

describe as “the finest detective in America.” The ruthless gangster soon

learned why.

According to It Happened in North Carolina, Scotti Kent’s

2000 book detailing several little-known episodes in the state’s history,

Littlejohn came to Charlotte from South Carolina in 1917 to run a shoe store.

Sometime in the 1920s, he went to work as an undercover federal agent

investigating Ku Klux Klan activities. In 1927, the Charlotte City Council

hired him to rid uptown Charlotte of prostitution. That position, originally

temporary, was the start of a 30-year career with the Charlotte Police

Department.

By the time of the mail truck robbery, Littlejohn had risen

through the ranks to become chief of detectives. He was a tall, lanky man. He

smoked cigars, and even today, people who knew him talk about his big nose.

Some say his ego was bigger.

“He was not very humble,” says Ryan Sumner, the historian

who curated “Beneath the Badge,” the exhibit on policing in Mecklenburg County

at the Charlotte Museum of History. “He had a reputation for being good, and he

knew it.”

He was good.

“He was no fool,” says Johnnie Helms, 79, a retired officer

who went to work for the department in the 1950s when Littlejohn was chief of

police. “He was thinking next week while I was thinking today.”

Helms remembers Littlejohn as a tough but fair man who knew

his city and who had strong ideas of how its police department should be run.

He didn’t like to be told what to do; he had more than one clash with the City

Council throughout the years and ultimately was fired 15 days before his

scheduled retirement for publicly criticizing a council action.

And as a story in the book Charlotte Police Department

1866-1991 shows, he wasn’t one to let convention get in the way of closing a

case. Evidence told Littlejohn that a murder in the Myers Park neighborhood was

likely the result of a homeowner walking in on a burglar. Experience with

Charlotte’s more unsavory characters told him who his likely suspects were.

Rather than interrogating the suspects, Littlejohn called

their wives and girlfriends into his office. With the lights down low, he

peered into a crystal ball and began chanting a voodoo spell he remembered from

childhood. According to Charlotte Police Department, “One of the women began

swooning and screamed that the killer was her husband.”

Hot on the trail

When Touhy’s men hit the mail truck, all Littlejohn and his

men needed was a single clue to get the investigation rolling. They got it when

the car used in the robbery was discovered within hours of the crime just

outside the city limits. It was a brand new black Plymouth sedan that was

stolen from a home on East Morehead Street two weeks earlier. Maintenance

records indicated that since its last service, the car had been driven only

nine miles — almost the exact distance between the robbery and where the car

was abandoned.

“If it hadn’t any more than nine miles on it, it had to have

been hidden somewhere all that time,” Littlejohn explained in a Charlotte

Observer article published toward the end of his career. So he put a detective

in a car and told him to drive along every route leading to the holdup scene.

At the same time, he had postal carriers asking residents on those same routes

if anyone had rented a garage. “This was a mail robbery, you see, and the postal

inspectors were on it. … We rang every doorbell,” he said.

They found a woman on 10th Street who had rented a room to

two men. At first, they didn’t want to take it, she said, because it didn’t

come with a garage. She arranged for them to use her neighbor’s. But, she

added, every time the two men left the house, they headed west, on foot.

That information, combined with the fact that there were

still two robbers unaccounted for, sparked a search for a second hideout.

Case closed

A tip about an unfamiliar Packard spotted near where the

Plymouth was stolen sent Littlejohn to the second location. “I went tearing

out,” he said. “I came up to the door and heard my own police calls blaring

out.”

Whoever had been in the room left in a hurry. They didn’t

bother turning off the radio they had tuned to the police channel. Detectives

found a suitcase full of clothes, three steaks in the refrigerator, and, on the

table, a newspaper with the story of how Littlejohn found the car used in the

robbery. Littlejohn ordered his men to take every item, including the garbage,

to headquarters. There, he sorted out 27 bits of torn-up paper that, when

pieced together, formed a Chicago rent receipt.

“For 60 hours there, I didn’t have my shoes off,” Littlejohn

said. “I left here at 6 p.m. that evening and was in Chicago the next morning.”

The landlady at the rental property gave Littlejohn

descriptions that matched eyewitness accounts in Charlotte.

“The landlady said one of the men carried a violin all the

time,” Littlejohn said in the 1957 interview. “That was no violin. That was a

machine gun case!”

Between the descriptions and fingerprints lifted from beer

bottles found in the second hideout, investigators nailed the robbers’

identities. The ringleader was Basil “The Owl” Banghart, a notorious thief in

the Chicago area and Touhy’s right-hand man. His suspected partners in the

heist were Ludwig “Dutch” Schmidt, Isaac A. Costner, and Charles “Ice” Connors.

All four had long histories on the wrong side of the law.

Within two weeks of the robbery, three of the suspects were

behind bars; one was dead. Investigators tracked down Banghart in Baltimore. He

was arrested and, six months after the holdup, stood trial in federal court in

Asheville. He was sentenced to 36 years for his role in the robbery. Costner

testified against his cronies but still got 30 years. And Schmidt pulled almost

30 years.

Ice Connors never made it to trial. According to The

Charlotte Observer article, he “was found dead in a Chicago suburb, his body

riddled with machine gun bullets and trussed with barbed wire, his dead fist

clenched around a penny.”

Littlejohn explained in the 1957 article: “That’s the

underworld sign for betrayal. Maybe Ice was just dumb, but he put the police on

the mob’s trail and that was enough to kill him.”

No-nonsense character

For his role in solving the crime and helping to put Touhy’s

top associates behind bars, Littlejohn received a letter from J. Edgar Hoover

in which the legendary FBI director praised him “as the finest detective in

America.” The framed letter adorned Littlejohn’s office throughout his career

with the Charlotte Police Department, which included 12 years as chief of

police.

Say the name Littlejohn to anyone who knew him or is

familiar with his history, and you get the same reaction: He was a no-nonsense

character, a poster boy for hard-line law enforcement. Helms, who walked an uptown

beat in his early days on the force, remembers the chief as a man who spent

little time at his desk and who knew everything about his city.

As the voodoo story demonstrates, Littlejohn wasn’t above

using questionable measures to solve a crime. Yet, Charlotte Police Department

1866-1991 credits him with setting the police department on a course toward

more professional law enforcement. He established Charlotte’s first police

academy; before that, new recruits were handed a gun and a badge and put on the

streets. He sent commanding officers to the FBI National Academy and the

Southern Police Institute. He set up the first youth bureau in the state to

address juvenile delinquency, and the police department established its first

firing range under his reign.

Littlejohn had high expectations for his officers, Helms

says, but he had the respect of his men and of the townspeople.

Persistence and perception

Even with those accomplishments, Charlotte’s “crime of the

century” and his role in solving it remained a highlight of Littlejohn’s

career. It shows up in most references to the chief.

Littlejohn enjoyed the recognition and recounting the drama,

no doubt. But apparently, the way he saw it, putting together the pieces of the

puzzle was just a part of the job.

“People have an exaggerated idea of the acumen and brains a

case like this takes,” he said in 1957. “Mostly, it’s persistence … persistence

and perception, which is different from observation.”

271 F.2d 261: Isaac Allen Costner, Appellant, v. United States of America, Appellee

United States Court of Appeals Sixth Circuit. - 271 F.2d

261

Oct. 22, 1959

Robert I.

Doggett, Cincinnati, Ohio, for appellant.

Russell E. Ake,

U.S. Atty., argued by James Sennett, Jr., Asst. U.S. Atty., Cleveland, Ohio,

for appellee.

Appellant and

one Barney Majjesie were charged in the District Court in a three-count

indictment with (1) possession of a 300-gallon still which had not been

registered according to law, (2) engaging in the business of a distillery

without having given the required bond and (3) fermenting 275 gallons of mash

fit for distillation in violation of Title 26, 5174(a), 5606 and 5216,

respectively, of United States Code.

Majjesie

entered a plea of guilty.

Appellant

waived a jury and was tried by the Court. He was convicted on all three counts

of the indictment. He was sentenced to two years imprisonment on the first and

second counts, to be served concurrently, and one year and five months on the

third count, to be served consecutively after the sentences on counts one and

two had been served.

Appellant was

represented by counsel of his own choosing in the District Court and in this

Court by counsel assigned by the Court. He filed his own brief in this Court

Twelve

questions were presented here by the appellant, many of which have no bearing

on the issues in this case.

The principal

error relied on in argument was that the judgment of conviction was not

sustained by sufficient evidence.

A motion for

judgment of acquittal was made by appellant at the close of the Government's

evidence. It was not renewed at the close of all the evidence.

Under the

circumstances this Court was not required to review the evidence. Picciurro v.

United States, 8 Cir., 250 F.2d 585. While not obliged to do so, we

have, nevertheless, examined the record and find no merit in appellant's

contention as there was ample evidence to support each and every element of the

several offenses.

The District Court

had before it eyewitnesses who saw appellant purchase quantities of sugar and

grain at different stores. He also purchased a pressure tank, still parts and

half-gallon jars which he transported to the site where he constructed and

operated the still. His own partner in the venture, Barney Majjesie, testified

against him. A Government chemist determined that the mash had an alcoholic

content of 3.4% by volume.

Appellant also

testified as a witness in his own behalf and denied the material charges in the

indictment.

He did not

recall buying as much sugar as was claimed, but did admit purchasing some

supplies for Majjesie, including sugar sweepings. He was arrested on the scene

by Government agents who had a search warrant.

It was for the

trial judge to determine who to believe under the circumstances and we cannot

say from this record that he was wrong.

Appellant next

contends that only one offense was committed and that the sentence on the third

count should have been made to run concurrently with the sentences on counts

one and two. In our judgment, different evidence was required to establish

count three. It was, therefore, a separate offense. Bozza v. United States, 330 U.S.

160, 67 S.Ct. 645, 91 L.Ed. 818; Newman v. United States, 6 Cir., 212 F.2d 450; United States v. White, D.C., 156

F.Supp. 37.

14

Appellant

further contends that his sentences were excessive. This was a matter solely

within the province of the District Judge and with which we have no right to

interfere so long as they were within the statutory limit. Hunter v. United

States, 6 Cir., 149 F.2d 710 certiorari denied 326 U.S.

787, 66 S.Ct. 472, 90 L.Ed. 478. The Court had the right to take

into account appellant's past criminal record which included two violations of

the National Prohibiton Act and one robbery of the mails for which he received

a sentence of 25 years in 1934. He has admitted violating his conditional

release.

15

We have

considered the other errors charged and find them to be without substance.

16

The judgment of

the District Court is affirmed.

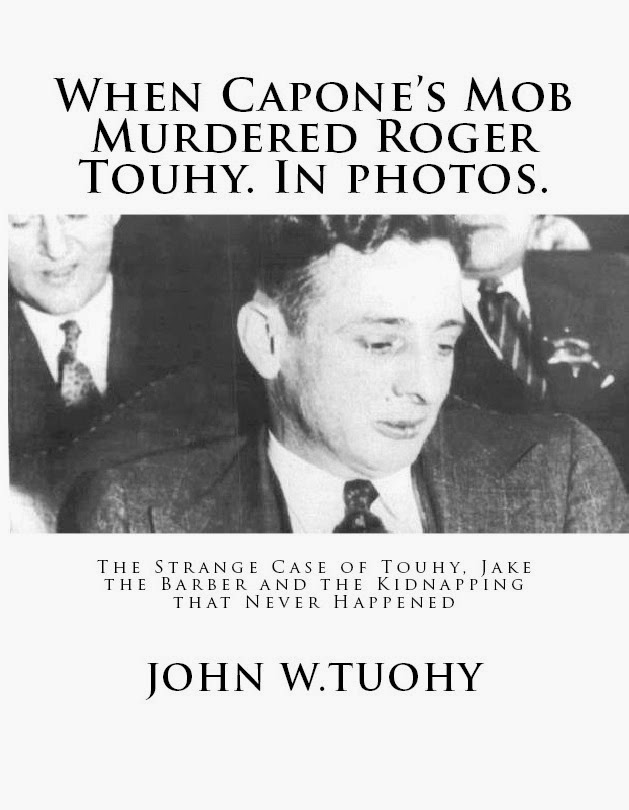

The Stolen Years by Roger Touhy. In public domian.

ROGER TOUHY

The Stolen Years

THE

STOLEN

YEARS

STOLEN

YEARS

By Roger Touhy

with Ray Brennan

with Ray Brennan

Copyright 1959, by Pennington Press, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book,

or parts thereof, in any form.

Library of Congress Number: 59-13425

Printed by Merrick Lithograph Company, Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.A.

To innocent men and women in prison, or otherwise deprived of their liberties, this book is dedicated. Roger Touhy

Acknowledgments

To Robert B. Johnstone, a brilliant and resourceful lawyer, my deepest thanks. He sacrificed a law practice and impaired his health in my behalf.

To Governor William G. Stratton and the members of the Illinois Pardon and Parole Board, I give thanks for their mercy and understanding. To the many lawyers who believed in me and fought for me, including: Daniel C. Ahern, Homer Atkins, Howard Bryant, Frank Ferlic, Frank J. Gagen, Jr., Kevin J. Gillogly, Joseph Harrington, Thomas Marshall, Thomas McMeekin and Charles P. Megan.

To the newspaper, radio and television people who brought the truth about me to the public when truth was what I needed desperately. They include: Earl Aykroid, Julian Bentley, Ray Brennan, Elgar Brown, Tom Duggan, Gladys Erickson, William Gorman, Jim Hurlbut, James P. Lally, Clem Lane, Robert T. Loughran, John J. Madigan, Milton Mayer, John J. McPhaul, Len O'Connor and Karin Walsh.

A number of police officers assisted me. Among them were Bernard Gerard, Thomas Maloney and Walter Miller. Without the diligence of Morris Green, my innocence might never have been established. To State's Attorney Benjamin S. Adamowski, my special thanks for telling the Pardon and Parole Board that he believed I should be freed.

Roger Touhy

“The court is of the opinion and finds and holds that the writ issued out of the Criminal Court of Cook County, Illinois, whereunder Relator Roger Touhy is held for the period of ninety-nine years for the crime of kidnapping for ransom is void because issued on a judgment of that court which is void because the proceedings in that court antecedent to said judgment and said judgment were violative of the Due Process of Law Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States in that said judgment was procured by means of the use of testimony known by the prosecuting officers to be perjured and because the Relator was deprived in a capital case of the effective assistance of counsel devoted exclusively to protection of Relator's interests and compelled against his will and over his protests to accept the services of counsel who was compelled to serve adverse interests.”

Judge John P. Barnes

United States District Court

Northern District of Illinois

August 9, 1954

CONTENTS

1. The Sharpest Thief in Stateville 19

2. Over the Wall 34

3. 82 Days AWOL 50

4. My Father Was a Cop 75

5. My Beer Was Bootleg-But Good 95

6. Al Capone Didn't Like Me 104

7. The Labor Skates and I 120

8. Jake the Barber Was Kidnaped??? 140

9. Nobody Questioned Me 155

10. Gone Fishing 170

11. Fiasco at St. Paul 192

12. Washington Gets Into the Act 206

13. What Jake the Barber Said 216

14. Alice in Factorland 225

15. A Hung Jury -- and Hope For Me 233

16. The Witness Who Wasn't There 246

17. I Get 99 Years 257

18. My Stolen Years in Prison 266

19. Enter Johnstone — and Hope Again 280

20. My Vindication in Court 291

21. A Great Judge's Opinion 302

Epilogue 329

1. The Sharpest Thief in Stateville 19

2. Over the Wall 34

3. 82 Days AWOL 50

4. My Father Was a Cop 75

5. My Beer Was Bootleg-But Good 95

6. Al Capone Didn't Like Me 104

7. The Labor Skates and I 120

8. Jake the Barber Was Kidnaped??? 140

9. Nobody Questioned Me 155

10. Gone Fishing 170

11. Fiasco at St. Paul 192

12. Washington Gets Into the Act 206

13. What Jake the Barber Said 216

14. Alice in Factorland 225

15. A Hung Jury -- and Hope For Me 233

16. The Witness Who Wasn't There 246

17. I Get 99 Years 257

18. My Stolen Years in Prison 266

19. Enter Johnstone — and Hope Again 280

20. My Vindication in Court 291

21. A Great Judge's Opinion 302

Epilogue 329

Chapter I

The Sharpest Thief in Stateville

The best thief I ever knew, in or out of prison, was Gene O'Connor. He was doing his stealing when I first knew him in Illinois' biggest and toughest penitentiary, Stateville, near Joliet. A wheelbarrow was all the thievery equipment he had; that, and a lot of good will.

O'Connor was a little man—smaller than I am, which is five feet six inches. He had an engaging grin and a disarming manner, and he was thinking all the time. Escaping was what he thought about mostly.

He was on a prison yard detail, which gave him the run of the joint. He buzzed in and out of the storerooms, the shops, the kitchen and the cell houses like a fly through a window with the screen left out.

I was working in the kitchen as a steward and clerk, and he would come around to mooch a cup of coffee, an apple, a handful of raisins or whatever he could glom. He hinted about escaping, but I didn't pay much heed. There were 3,000 cons in Stateville, and all of them had crazy ideas about going over the wall.

"You're too busy stealing in here to take time to escape," I told O'Connor. "You're doing better in stir than you could on the outside."

Two or three times a week I would see him pushing his wheelbarrow across the yard toward one or another of the guard towers. He would be trundling a quarter of beef, steaks, slabs of bacon, a 100-pound sack of sugar, or bags of coffee.

He stole the stuff out of the storehouses and peddled it to the guards in the towers. Those towers are perched on top of the prison wall, which is 33 feet high, of solid concrete and steel, and nine feet thick at the base. Each guard up there has a cubicle to sit in, with windows looking down on the yard and a catwalk for exercise along the top of the wall.

The only square way to reach a tower is by an enclosed stairway on the outside of the wall with a solid door kept locked at the bottom. When O'Connor reached the inside base of the wall at one of the towers, he would call up to the man on duty.

The screw would lower a rope and Gene would tie on the loot for the trip. Up would go beef, coffee, bacon or sugar. The tower screws dropped a dollar or two for Gene now and then, or mailed letters to his outside connections for him. But mostly he was making friends and building up good will.

The year was 1942 and the guards were old parties brought in to replace younger men who left for the armed services or for big-paying jobs in war plants. They probably never understood what a hell of a chance they were taking with O'Connor. The damnedest prison break that ever happened at Stateville was in the making.

Gene kept giving me reports about the jolly, larcenous friends he was making in the towers, and the "influence" he was building up. Wartime rationing was on and the guards were getting big money—considering the starvation wages paid in all prisons—by selling O'Connor's meats and groceries in the Joliet and Chicago black markets.

First and foremost, I was under a sentence of 99 years. I would have to serve a third of it, or 33 years, before even being allowed to apply for parole. I had a minimum of 25 years left to go before parole, and I didn't want to stay alive that long in prison—even if I could. So what did I have to lose by going over the wall—or getting killed trying?

Also, "One old character up there is treating me like a son,"' O'Connor told me. "I said to him this morning that I was coming up to visit him some day. He told me to come right ahead and bring my friends. He said he never shot anybody in his life and he wasn't aiming to start now."

I didn't want to know about such things and I told O'Connor so. Convicts have a saying that goes: "If three guys know a secret, that makes four, counting the warden." I didn't relish getting a rap as one of the three guys who got word to the fourth.

Anyway, O'Connor kept on stealing everything that wasn't nailed down, and some things that were. He got away with it because we had a dull warden and a lot of new guards. And he kept needling me to throw in with him on the escape. I was a good candidate for a break, by his standards.

First and foremost, I was under a sentence of 99 years. I would have to serve a third of it, or 33 years, before even being allowed to apply for parole. I had a minimum of 25 years left to go before parole, and I didn’t want to stay alive that long in prison—even if I could. So, what did I have to lose by going over the wall—or getting killed trying?

I had been railroaded to prison. I was innocent. I had been convicted of a fake kidnapping that never happened. I had been sworn into prison on false testimony. I was a fall guy for the Chicago Capone mob. I was rotting in prison on the falsified testimony of a swindler and ex-convict, John “Jake the Barber” Factor.

A distinguished former Federal judge, the late John P. Barnes, subsequently ruled that the kidnapping was a hoax. I had been railroaded to prison under an unjust conviction. Even so, I should have continued to be deaf when Gene O'Connor talked to me. Instead, I was dumb--stupid dumb.

He came to me one day in early summer, and he was grinning with good news. I was in the kitchen and he was pushing that silly wheelbarrow. It was half full of sand. They were drilling a well in the yard and some of the sand from the hole was going into the bottoms of decorative tanks of goldfish in the big dining hall. O'Connor sidled up to me and whispered: "We got two guns into the joint last night, Rog. Old Percy Campbell carried 'em in wrapped up in the flag."

I was shocked and scared. Guns in a prison are like a firebug in a high octane gasoline refinery. I backed off from Gene and told him to keep the hell away from me. There was no reason for me to be thinking seriously about a break at that time. I had something going for me, and I wasn’t hopeless. Not even desperate. I figured I had some percentage on my side.

John P. Lally, a Chicago Daily News writer, had made up his mind that I was innocent. He was one of the first of many to realize the truth. He worked day and night on my case, digging up evidence. He had visited me a few months before with this message: “Rog, you never will spend another Christmas in this place."

One of Lally's Daily News co-workers, William Gorman, had written a long magazine story on my case. I had read the story. It was a good one, and it showed my innocence. When it was published, Gorman and I figured, public opinion wouldn't allow me to remain in prison any longer. I had the greatest possible confidence in the article.

After O'Connor dropped the word about the guns and left me, I stood in the kitchen doorway for quite a while. It was the first really fine day of early summer. Acres and acres of flowers were blooming in the prison yard, where Warden Joseph E. Ragen had had them planted before the politicians got rid of him, temporarily —and I, Roger Touhy, got him back. In Joliet, down the road a piece, the pretty girls would be out in their sleeveless, summer dresses. It was the kind of day when convicts, all 3,000 of us in Stateville, began to get restless. Nature makes guys that way in the spring, I guess.

I was thinking of my wife, Clara, the little brunette I had courted by telegraph when we were both youngsters working opposite ends of a Morse wire for Western Union in Chicago. Our two sons now were high-school age. They weren't having it easy, I knew. This was my eighth year away from them; a hell of a long eternity when you measure it on a penitentiary calendar.

As I stood there in the doorway, birds were singing from every direction, from the flower beds, the shrubbery, and from trees in the yard. There were thousands of birds in Stateville, and more every year because the cons fed and protected them. We envied them, too, and sometimes our feelings got pretty close to hatred. A bird can go over those 33-footwalls faster than a tower screw's rifle can follow and be miles away in minutes. The cons protected the birds, and any hungry cat caught sneaking up on a robin or a bluejay could expect a kick in the tail in Stateville. Still—with the temptations of birds, family, spring time and all—I had no thought of joining Gene O'Connor. I had faith in Gorman and his magazine story. I remembered the promise that I'd be out by Christmas.

All through the hot summer and into the fall, O'Connor needled me. The two guns were hidden somewhere in the prison, he kept saying. The break couldn't miss. Basil Banghart was going along. The old tower screw wouldn't shoot.

Gene's news bulletin about Banghart impressed me. Basil was a shrewd, fast-thinking con. Everybody called him "The Owl" for two reasons. He had big, slow-blinking eyes, and he was wise. He wouldn't go on a break unless the gamble was a good one. I had met him for the first time in Stateville.

The Owl had been sentenced to 99 years for the Factor kidnap fake, as I had. He was a resourceful and courageous man. He could run a locomotive or fly an airplane, and he was better than a green hand at opening up an armored mail truck or persuading a bank guard not to step on the robbery alarm button.

O'Connor was no slouch, either. He had beat Stateville twice on breaks. Once he got into the powerhouse at night, pulled a switch that doused every light in the prison, got a ladder from the carpenters' shop, and whisked over the wall in darkness. Another time he had himself nailed inside a furniture crate being shipped to Joliet, and rode through the gates in a truck.

"This is going to be a high-class break, with no dummies allowed in the group," O'Connor assured me. Sometimes he talked like those Ivy League Madison Avenue boys who started getting into Stateville after they lowered the entrance requirements to include Phi Beta Kappa men. He also explained the exact way in which the two guns had been smuggled in.

Percy Campbell was an old trusty who pottered around outside the main gate, tending the flower beds, watering the grass, sweeping the walks and tidying up the visitors' parking area. He also had the job of carrying in the American flag at sundown every day.

The guns were left at the base of the flagpole one night and Percy carried them in next evening, wrapped up in Old Glory. He got a grand total of thirty bucks for this errand. Whatever his other talents might have been, Campbell was an amateur at collective bargaining. I guess Percy did it mainly for meanness. He had put in 17 years on a one-to-life term, and he should have been paroled long before.

I was an unwilling listener while Gene talked, but that was all. O'Connor wanted me along so bad that his urging got to be a nuisance. I had friends and political connections on the outside. I could raise money and arrange for hideouts, he figured. I just shook my head "no" and grinned.

And then the bad news began hitting me. First it was Lally, of the Chicago Daily News. He died of cancer of the throat. Not only had I lost a good friend, but one of my last two legal chances to get out of Stateville was gone. I had some outside people send flowers to John's funeral. That was all I could do.

John died without ever telling anybody what evidence he had found: why he was so certain I never would spend another Christmas in prison. He wanted his story to be exclusive and, like any good newspaperman, he kept buttoned up.

Chance No. 2 blew up when Gorman came to see me. I knew at once that something had gone wrong. He was carrying a large brown envelope, and his face was long. "I'd rather be kicked all the way back to Chicago than tell you this, Rog," he said. He dumped the contents of the envelope in front of me. Magazine rejection slips, dozens of them.

"No magazine will take the story," Gorman said. I read a few of the slips. Some of the editors wrote that they were interested only in articles with a war angle. Others said that the story of my doublecross was too fantastic, that readers wouldn't believe it. One editor commented coldly that all prison inmates claimed to be innocent and that most of them were trying to get their alibis into print.

I mumbled my thanks to Gorman for all of his wasted work. I stumbled back to my cell. I was seeing through a sort of haze. My last hope was gone. The United States Supreme Court earlier had turned me down for a hearing. I wasn't a man any more. I was a dead thing. I stayed awake until dawn in my cell, thinking. I was without hope. I was buried alive in prison and I would die there. I couldn't see a light ahead anywhere. Nothing but darkness and loneliness and desperation. The world had forgotten me, after eight years. I was a nothing.

Well, there was one way I could focus public attention on my misery. I could escape. I would be caught, of course, but the break would show my terrible situation.

What cockeyed thinking that was. The only thing I could do by going over the wall would be to destroy almost every chance I might have for decent justice at some future time. But a man in my spot isn't reasonable, of course.

My mental attitude was a mess, I later came to realize. I hadn't seen my wife, Clara, for four years, but I couldn't forget her last visit. It had been an ordeal rather than the usual delight. She had worn a white hat and gloves and a dark tailored suit, I remembered. It might be a long time before I saw her again, and maybe never.

At that time, in 1938, I had been disconsolate. I had figured that I couldn't be a drag on Clara and our two sons for all of their lives. So I had given her a direct order for the first time in our 18 years of marriage: "Take all the money you can raise and go to Florida. Change your name. Take the kids with you, of course. Start them out in a new school down there under new names. This is something you must do. "I'll be in prison for a long time. I want you to make a fresh start for all of us in Florida."

I gave her the names of a couple of people she could trust completely in Chicago and in Miami. They would help her get started in this new life. I would send word to her and the boys through the contacts, and get messages from her.

Her eyes filled with tears, but she didn't cry and she didn't ask a lot of questions, either. Giving her that order was the most difficult thing I ever did. But it had to be done, I thought. She had only one question to ask as she sat across the long table in the visiting room, forbidden by the rules to so much as reach across and touch my hand for a goodbye.

"When should the boys and I leave for Florida?" she wanted to know. I told her right away, the next day, if it was possible. The visit was over, and when I looked back from the door, she was staring at me. I think she was crying, but somehow she put on a smile.

Anyway, after my last hope collapsed in 1942, I decided to throw in on the escape. I was thankful then that Clara and the boys were out of the way, living in obscurity under the name of Turner in the Florida town of Deland.

Once I was over the wall, or killed trying to get there, the publicity would be monstrous, with newspaper headlines the size of boxcars. I didn't want my wife and kids hounded by the police or the FBI; I wouldn

't be able to see my family, anyway. They would be watched, if the law could, find them. Their mail and telephone would be checked. I would have to avoid them like yellow fever wherever they were—Chicago or Florida or the other side of the world.

After making up my mind to go AWOL, I passed Gene O'Connor in the yard and told him: "I'm going with you."

He didn't seem a bit surprised then, or later, in the kitchen, when he gave me a rundown on the program. He pointed to one of the guard towers and said that was where we would go over the wall. He set the time for one P.M. on October sixth.

"The screw up there is the old guy who says he won't shoot anybody," Gene said. "I'll promise him the day before the break to bring him some meat and groceries. That way he'll be sure to have his car beside the wall outside, to take home the stuff. We're using his car."

O'Connor explained exactly what I had to do, and it didn't sound too tough. But not easy, either. October sixth was three days away, the longest three days I ever lived. I ate and pretended to sleep and acted like I was interested in the radio broadcasts. And all the time the only thing on my mind was how a rifle bullet from one of the guard towers would feel drilling into my back.

Then, with only ten minutes’ notice, O'Connor called everything off for another three days. The new date, October ninth, was the one he had in mind all along. I had jittered for three days for nothing.

I asked him the reason for the fake date and time, and he explained. It had been a pretty clever idea, at that—he had been testing the security of the plan. "Suppose somebody had stooled to the warden that the break was coming off on the sixth," he said. "The warden would have cancelled all days off for the screws, and I would know he was wise. Then I could have nosed around, found out who talked too much, dealt him out of the break and made a scheme to use the guns later in some other way."

Gene could have been a great commanding general or an international spy, if he hadn't preferred being a thief.

I asked him then for the first time who was going on the break and he told me—Banghart, Eddie Darlak, Martlick Nelson, Ed Stewart and St. Clair Mclnerney, plus the two of us. Ours were names that were to hit the headlines for nearly three months.

Eddie Darlak was a Chicago man doing 199 years for murder in a cop-killing conviction. I knew him slightly. He had to go with us, Gene said, because his brother had delivered the guns to the flagpole. That sounded okay; 23and I was in favor of "The Owl" being with us, of course.

Nelson, Stewart and Mclnerney meant nothing to me, but I might have seen them around Stateville. It was impossible to know 3,000 men, all dressed the same way, and without identifying marks such as mustaches or preferences in neckties.

A short time after lunch on the big day, I was standing at the back door of the kitchen, following out Gene's plan. A truck came rolling along on the daily round, picking up garbage to be hauled to the prison hog farm outside the wall. I was trembling like a kid on the way to the woodshed for a whipping.

I walked up beside the driver and asked him for the truck keys. He looked at me like I was crazy—and he wasn't far wrong. "Give me the goddamn keys," I told him, and it surprised me to hear my voice and realize I was yelling. He pointed to the truck's instrument panel; the keys were hanging from the ignition switch. I pushed and pulled him out of the cab.

The driver said later that I waved a big scissors from the tailor shop at him. That wasn't true, but I didn't blame him for saying it. He might have got hooked on a phony aiding-and-abetting-to-escape charge if he hadn't told a real good story.

I drove the truck along, slowly and carefully, getting the feel of driving after eight years. There was a steel mesh cyclone fence running across that part of the yard and I had to get through a gate where a con was on duty.

After about 75 yards, I approached the gate and beeped the horn. The gate swung open at once. The inmate waved me on and closed the gate. To him, this was just the garbage truck making a routine run.

I stepped on the gas a little. Straight ahead of me was the mechanical store, a building with a vehicle ramp leading down under it. The prison coal supply and a lot of equipment were there. I made a U-turn and backed the truck down the ramp.

O'Connor, Banghart, Darlak and the other three were waiting for me. So, it seemed to me at first, was about half the rest of Stateville's population, although there really were only about 300 cons crowded around.

Two of our guys—Darlak and Banghart, I think—were holding guns, and they had a complication. A guard and a staff lieutenant were down in that passageway under the building. They were standing with their hands at their sides and their faces were white. We were no more scared than they were, really, and for good reason: many a guard held as a hostage has been killed in a prison break.

Somebody handed me one of the guns, a .45. The others loaded a heavy ladder in two extension sections onto the back of the truck. We put the lieutenant and the guard on top to act as ballast and hold down the ladders. I climbed up with them.

Stewart was behind the wheel of the truck and I heard the starter grind a couple of times. The engine didn't start. I jumped off the back of the truck and took Stewart's place. It still wouldn't turn over and I hollered: "The goddam thing is stuck on center! Push it, you guys."

Those convicts down there with us grabbed the truck in every place there was a handhold. They pushed it and rocked it, anxious to help. The motor came off dead center and started at last with a roar.

I drove up the runway and aimed the truck at the tower where the old father-and-son screw was on duty. It seemed to me that we were going 90 miles an hour, bucketing across the yard. The convicts who had helped start the truck cheered and waved to us. Two 50-gallon oil drums, for garbage, were on the truck. I hit a big bump and those drums shot out across the yard like depth charges from a Navy destroyer. It was a crazy trip, and things were going to get crazier.

Chapter 2

Over the Wall

I skidded the truck to a stop near the wall tower. We unloaded the ladder, and then things went comical. Nobody knew how to fit the two extension lengths together. Each guy tried to do it in a different way at the same time, with everybody swearing at each other.

Another guard lieutenant came ambling up. He seemed upset, but not much. "You sonsabitches," he said, "don't you know them tower windows ain't supposed to be washed from the inside?"

I started laughing so hard I could hardly hold the .45 on him.

He finally saw the gun. His mouth fell open and he went over and stood with the other lieutenant and guard. One of the screws kept saying, over and over: "Let 'em go. Don't interfere. They'll kill us for sure."

The three of them were helpless against us. Guards and officers went unarmed, except for blackjacks and clubs, inside Stateville. They used to have weapons, but the state lost too many guns that way, with the cons taking them away from the screws. But the old lad up in the tower had plenty of firepower, 26and I got to thinking about him. The way we were flubbing around with the ladder might give him brave ideas.

He might get hurt and so might we, which I didn't want. He was standing over to one side of the tower at the end of the walkway, doing nothing. He wasn't holding a gun, but he didn't have far to reach for one.

I decided a little noise might make things safer for everybody, including him. So I fired two shots and knocked out the glass of a window at the opposite end of the tower. He raised his hands and hollered that he was going to behave.

We got the ladder in place, at last, and I scrambled up with the .45. The other six men in the escape party followed, with the two lieutenants and the guard spaced in between us. With the screws along, we had less danger of drawing fire, although maybe that precaution wasn't needed.

Not a shot came from any other tower. Either the screws weren't looking, or else they were remembering all those meats and groceries from O'Connor's wheelbarrows. It was pretty crowded when all of us got to the tower house, which was only a cubicle. The guard handed over his keys to his sonny boy, Gene, and croaked at him: "Please don't take me with you. I'm an old man." A couple of other guys got his weapons—a 30.30 rifle and an automatic handgun. On the floor of the tower were packages of meat and other stolen stuff that O'Connor had delivered a few hours before. The tower man's Ford sedan was standing on the roadway outside the wall waiting to haul the loot home—but now the script was changed. It was going to carry us far, far away, if our luck held.

The grandpappy guard had a scratch on his face, from flying glass, I guess. He sure as hell wasn't shot, as some people tried to claim later. The next thing that happened all but panicked me.

Gene gave the ladder a kick and it clattered down to the ground inside the wall. I started to yell that now we were trapped in the tower. Without the ladder, we could break our legs or necks dropping those 33 feet to the outside. Sure, there was a stairway leading down, but the door 27at the bottom would be locked, and there was a keyhole only on the outside. But O'Connor had covered that angle, too. "Thorough" was his middle name that day.

He dropped his grocery delivery rope over the side and somebody—Nelson, as I remember—shinnied down it. Then O'Connor dropped him a key, taken from the old guard, to the door below.

Some one of the guys tore the tower telephone out by the roots. That would delay the alarm getting to the warden's office and from there to the Illinois Highway Patrol. Then we tumbled down the stairs, locked the door behind us and piled into the guard's Ford.

I looked at my watch. It had been just 17 minutes since I took the garbage truck away from the driver—but it seemed like it'd been some time back in my childhood.

Banghart gunned our getaway car, and I looked back. The two lieutenants and two guards were gazing after us from the wall. They couldn't do a thing except yell for help. We had the tower arsenal, plus the two pistols that Darlak's brother had delivered to the flagpole.

We were on Highway 66 for a while, but mostly we hit the country side roads. After a while we pulled into a patch of woods to talk things over.

"Where do we go from here?" I asked. "Where's the hideout?"

There was a long silence. I began feeling silly, then alarmed and finally, downright mad. The situation was obvious—and awful.

We didn't have any place to go. There wasn't any hide-out. O'Connor, the master mind, hadn't set up even one single goddam contact to help us. We were in a mess. We had just pulled off one of the slickest prison breaks in history. And now we were as unprotected as a stranger turned loose at noon without clothes in downtown Chicago.

Seven of us were jammed into a small car. All of us were wearing prison uniforms. We had guns, but what good would they be against the army of cops who soon would be looking for us? What a fugitive needs is a place to hide, not firepower.

I had taken it for granted that O'Connor had made arrangements, at least for a few days, on the outside. He hadn't. Well, there was no sense in bellyaching. We took stock. Together we had $120, mostly money that Gene had picked up from his meat-and-grocery route.

What we needed was darkness, and it was hours away. In the meantime, we had to keep moving. The news would be on the radio soon, and every farmer or small town rube in Illinois would be phoning the cops upon seeing a parked car with a lot of guys in it.

So we drove. We kept to the dirt and gravel roads, driving carefully and slowly. When we met a car, some of us crouched down so we wouldn't seem to be so overcrowded. The car had no radio so we couldn't hear the news about ourselves. But one thing was good. The Ford had a full gas tank, so we didn't need a filling station stop. Nature's demands we handled in the trees and bushes. Everything was aimless. I remember noticing that we passed through one village four times. The name of the place was Barkley, and I got mighty weary of it.

When darkness hit, we pulled into a Forest Preserve grove near Lombard, a suburb to the west of Chicago. We had driven more than 150 miles and we still weren't anyplace. We did some scrounging and one of the guys got into a garage at the rear of a house. He came back with a tattered suit jacket and an old raincoat. The clothes fit Banghart pretty well, so he wore them into a grocery store to shop.

We ate bread, cheese and cold meat, washed down with milk. It felt fine to eat without a gun pointed at you from a dining-hall tower. "You should have brought a side of prison beef along," Darlak told O'Connor, "and we could have had a barbecue."

We had to have help, but where to try for it was a terrible problem.

The prison had complete lists, with addresses, of our relatives, of visitors we had had at Stateville, of people we had corresponded with. They would be watched, with taps on their telephones. Former cell mates and friends on parole would be covered like a floor with wall-to-wall carpeting. Anybody who did help us could be prosecuted for harboring criminal fugitives.

There was one possibility among all the hundreds of people I knew in Chicago. He was a legitimate businessman and he had been my friend since we were boys. He never had been in trouble with the law, and there was nothing kinky in his background. But, most important, we never had communicated when I was in Stateville, so the prison had no line on him. I felt sure he would help us if we could get to him.

The Owl, wearing the tattered jacket and old raincoat, rode a bus into Chicago. I gave him instructions on how to telephone the man I had in mind. I couldn't make the trip because the clothes from the garage were acres too big for me.

The rest of us waited through the night. It was bitter cold, even for October in the Chicago area. We couldn't take a chance on lighting a fire. "If Banghart doesn't score," Mclnerney said, "we might as well go back to the main gate at Stateville and apply for re-admittance."

But The Owl didn't fail us, and neither did my friend.

Soon after dawn Banghart was back. He was driving a car and carrying $500, both loaned to him for me by the Chicago businessman. And in the car were pants, jackets, shirts and neckties—nobody ever expects to see a necktie on a con—enough so we all got a good enough fit.

We dressed and were ready to take off for Chicago in the borrowed car. But Gene got to feeling sorry for the old tower guard and his Ford sedan. If we left the Ford in the grove, O'Connor said, it might not be found for a long time. What would the screw do for transportation?

"I'll drive the car up on the main drag of Lombard and park it there," our master-mind said. "That way it will be spotted in a couple of days. You follow me and pick me up."

In a couple of days, it would be spotted, he said! Less than a couple of minutes! The license numbers of that Ford had been going out over the police radio every ten minutes all night long. Every cop in the Midwest was looking for it, slavering frothily for a reward and dreaming of becoming a hero. That car was hotter than a jet plane's after-burner.

We had no more than turned the corner after O'Connor parked the guard's heap and rejoined us when there came the big "w-o-o-o—woooo" of a police car siren. A suburban squad had spotted the license. But by that time we were out of sight.

I turned on the radio in the new car and got the police wavelength. The broadcasts made us feel real good. We had been reported seen in St. Louis, Indianapolis, Kansas City, Peoria, and 14 different places in Chicago. The cops had us pinpointed just about every place in the Midwest except where we really were.

All the way into Chicago we didn't see so much as one police car. If the police had us blocked off, as the radio kept on saying, then somebody had left a great big hole in the roadblock.

"I got more good news for you," Banghart said, as we turned in on Ogden Avenue, the diagonal street leading from Joliet and the Chicago Midway Airport into the Loop. "Rog's friend has lined us up for an apartment. We can move in right away."

We went there, and what a miserable dump it was. A basement flat near 13th and Damen.

I knew the neighborhood like a penitentiary screw knows his stool pigeons. I had played stickball in the streets out there as a kid, pestered the hurdy-gurdy man, and opened the fire hydrants for cooling off on those 100-degree August days.

We went into the apartment. Warden Ragen wouldn't allow a pig from the Stateville farm to set one cloven hoof in the place. The walls were sweating with dampness. The kitchen crackled everywhere we stepped. Roaches were a carpet on the floor.

And the rats! They were as big as tiger cubs and twice as nasty. Banghart claimed that one of them—a stallion rat, he said—stood up on his hind legs, doubled up one fist, pulled a switchblade knife in the other and told him, with the authority of a Stateville guard captain: "Get outa here, you bastard, and take your friends with you. I've been boss of this cellar for 20 years and you ain't going to muscle in”.

I believed The Owl. And the rat, too. But we had nowhere else to go. We stayed after Banghart said: "We'll plug up the holes in the floors and the walls with steel wool, and let the goddam rats tear out their claws and teeth trying to burrow through." A great strategist, Banghart was—except when it came to staying out of prison.

The landlord of the building was an elderly man who lived in a cottage at the rear. We told him we were from downstate Illinois, in Chicago to go to work in a war plant. He took $65 for a month's rent and told us where we could buy cheap furniture in a second-hand store somewhere on Madison Street.

We got in some groceries and, for the first time, we saw the newspapers, all editions of them since the previous afternoon. Our escape was the biggest news anywhere in the world, so far as Chicago was concerned. We had pushed the war off page one. The big, screaming headlines would make you think we had murdered half the guards in Stateville.

The Owl and I got the biggest play because we had been in the headlines for our conviction in the fake Jake the Barber Factor kidnapping. Our pictures were plastered all over the papers, but they were eight years old or more and we had aged a lot in prison. O'Connor killed my optimism along that line by saying: "Sure, you guys are older, but you're just as homely, if not more so. Any cop could recognize you from the photos, and don't forget there'll be rewards out for all of us soon."

In its very first story of the break, one of the papers had dug up the tag of "Terrible" Touhy for me. That fitted me like calling Calvin Coolidge an anarchist. The only conviction I ever had in my life, up to the time of the Factor frame-up, was for parking my car too close to a fireplug. And now, the papers were speculating on how soon I would lead my "mob of terrorists" into robbing a bank or kidnapping somebody.

Out in California, on a fancy estate built out of swindling people, Jake the Barber was bleating like a lost lamb and trying to look twice as innocent. He was scared as hell that Banghart and I would kill him, he said, and the FBI was guarding him. Huh! I wouldn't spit in his direction, much less touch him.

Factor then was under indictment, but on bond, for swindling Catholic priests in another of his fancy con games. He later served a prison term in the case, too. My silly idea of bringing my case before the public for justice was rebounding in the newspapers like a screw's club off a convict's head. Instead of getting fair treatment, I was being crucified. There wasn't one mention in any of the papers that day that I might be innocent—although there were plenty of working reporters, even then, who believed in me.

Later there was a story by Bill Gorman in the Daily News, saying there probably had been no kidnapping, but nobody seemed to pay much heed.

I gave up reading and went for a walk. It was my first jaunt around Chicago since getting free. I looked at the show window displays, dropped in at a couple of joints for a beer and saw a movie. The thing I enjoyed most was looking at the people, free people. Heading back toward the apartment, I went into a Pixley & Ehler's Restaurant, one of a cafeteria chain specializing in baked beans. I got a crock of beans, Boston brown bread and coffee at the counter, went to a table, and started to eat. But I didn't relish the beans for long.

In the door came three of the biggest, toughest-looking coppers I ever saw. I froze. There wasn't any back door. I was like a mouse in the wainscoting with a cat plunked at the only exit.

The cops picked out their food and brought it to the table next to mine. One of them sat sipping coffee and looking at the Chicago Times, a tabloid. My picture covered practically all the front page. He squinted at the photo for a while.

"This guy Touhy would be a fine pinch," he said, and lit into his grub. He could have reached out and grabbed me almost as easily as he picked up his coffee cup. I finished my food, paid my check and left. A fine sense of well-being hit me. I wasn't scared any- more and I wouldn't be again. The experience had shaken the hell out of me; but, at the same time, it had given me back my courage.

Now, I knew I really was free. Nobody knows freedom, of course, if he has fear but I never thought of that before. Back at the apartment, things weren't good. Mclnerney, Nelson and Stewart had brought in whiskey and they were getting drunk and noisy. They were talking about going out to look for women. I told them to quiet down and act careful.

Mclnerney got mean and sneering. "Big shot, eh? Think you're going to run everything, do you?"

I put it on the line for them -- noise, whiskey and women would bring trouble, not only for them but for me, too, if I was living with them.

It was my money, part of the $500 I had borrowed, that they were drinking up. I wasn't being tough, but unless they stopped behaving like reform-school sophomores I was moving out.

I went to bed after that, but the next day I gave our situation a lot of thought. I wasn't going to gamble on going back to Stateville on a drunk-and-disorderly pickup. Anyway, living with six other convicts in a small apartment was too much like prison for me. I wanted solitude: a life of my own without unnecessary danger. For another thing, the men who escaped with me still had the guns we brought from the penitentiary. Suppose a cop came nosing around the apartment and one of the guys let loose with a pistol. A lot of people could get killed, and I might be one of them.

So I set up a life for myself. I was going to stay outside the wall just as long as I could. I would enjoy my freedom in my own way. I wouldn't carry a gun and, when the time came -- as it must for every fugitive -- I would give up.

I wasn't going to have anything to do with any shooting. I found a furnished flat behind a bank building at Madison and Ogden on the West Side. It was small, and the toilet-bath was a share-it proposition down the hall. But, the joint had two exits, which was essential to sound sleep for me, and the location gave me a boot. My, how those bankers would have shook if they knew "Terrible" Touhy was living only a few feet from their building!

When I got back to the basement apartment that evening, a drunken argument was going on. Mclnerney wanted to fight. I jollied him along and then said in a nice way that I was leaving for a place of my own. It was only fair to them that I move out, I told them.

The newspapers were running pictures of me every day. I was hot as a depot stove. If I got caught, so would the rest of them if they were living with me. I didn't really believe that guff, but it got me out of the basement without a fight. I made a deal with Banghart for contacts. To hell with the rest of them.

For a couple of days, I just sat around my new place, admiring the loneliness. It was terrific not to have- some con snoring or whimpering or yelling in his sleep in the same cell, or the next one. And no guard peering through the door with a stool pigeon pencil in his hand. The greatest pleasure in life is to be unregimented, your own boss. Prison teaches you that—though it isn't the easiest way to learn it.

I needed a substantial bankroll, just in case I had to pay off a bribe or get out of Chicago. My best source was my brother, Eddie. He owned a roadhouse, Eddie's Wonder Bar, near the State Fair Grounds outside of Madison, Wisconsin.

I had put up the money for the place, and Eddie would come up with any reasonable amount I needed. But making a meet with him was almost as tricky as getting out of Stateville. The FBI would be sticking as close to him as hogs to a swill barrel. His phones would be tapped. If he got caught with me, it would be a harboring rap for him.

(Editor’s Note: Other brothers included James Jr. who was killed during a mail robbery in 1917; John, who was accidently shot by one of his own men in 1927; Joe, who was killed in 1929 and Tommy. When Eddie died, ownership of The Wonder Bar went to Touhy’s sister.)

So, I called my friend, the businessman who had loaned me the car and the $500. We met in mid-afternoon at the Morrison Hotel bar and had a drink at a quiet table.

I explained what I wanted and he set me up with a guy. I'll call him Simpson, but that wasn't his name. Simpson was an ex-convict, and eager to pick up a quick buck. I explained what I wanted and even drew a map for him.

He drove up across the state line to Wisconsin, parked his car in downtown Madison so his license wouldn't get spotted and took a bus out to my brother Eddie's place. I figured I needed $1,500, but Eddie said to make it $2,500. He would get it from the bank the next day and send it by messenger to Chicago. Simpson came back to Chicago and he was itchy about the set-up in Wisconsin.

"There are a lot of guys acting like surveyors around your brother's club," he said. "They got spyglasses set up on tripods so as to get a fix if you try sneaking up to the joint across the fields or through the fairgrounds. They're FBI men. They hang around Eddie's bar and peek through the windows of his living quarters at night. I told him to have your messenger make damn sure he isn't tailed when he comes to Chicago."

I got the $2,500 the next day. An ex-convict working at the Wisconsin Fair Grounds brought it to me at my apartment, and he wouldn't take a dime for his trouble. Eddie was paying him, he said. He also brought word that Eddie wanted to fix me up with a hideout in Arizona. To hell with that, I said. I wasn't going to bury myself in some hole in the desert. I was staying in Chicago. I had plenty of money now and things should go better. But a lot of problems and troubles were ahead.

(Editor Note: Eddie Touhy died of natural causes in 1945. In 1917, he was sought in questioning relating to a $20,000 mail robbery with Spike O’Connell and Tommy Touhy.)

Chapter 3

82 Days AWOL

82 Days AWOL

A convict on the lam absolutely must have a set of identification papers. A Social Security card. A driver's license. And, back in 1942 when I was loose—a draft card. With such papers, a man usually can talk himself out of a routine arrest. Without them, he is up against a trip to a police station—with identification by fingerprinting—for any trifling thing the cops may ask about.

I was living in a semi-Skid Row section of Chicago, losing myself among thousands of men trying to be forgotten for reasons of wife-trouble, personal disgrace, a permanent knockout by booze, or just plain shiftlessness.

This jungle of men gave me a fine protective coloring, but there were drawbacks. The cops might collar a man —me, for instance—at any time for a few questions. The FBI was looking for draft dodgers and the military authorities for wartime deserters. Also, I needed a car to get around, and passing a traffic sign could mean a return ticket to Stateville unless I had a driver's license.

I hit on the deal that a pickpocket could fix me up, and I knew where to find one. He was a skinny little guy, and I had seen him get run out of a Monroe Street joint by a saloonkeeper who hollered at him: "Get out of here, Slim, and stay out. You've lifted your last wallet off my customers."

I watched for this character and saw him about a week later as he waited for a streetcar. When I asked for a word with him, he held his arms out from his sides and said: "Okay, officer, give me the frisk. I'm clean. Haven't made a touch in months."

It took a little talking to persuade him that I wasn't a detective, and then we went into a little restaurant for coffee. I told him a tale—one he obviously didn't swallow —that I had walked out on my wife and that I needed driver's license, Social Security and draft registration cards. He wanted to know how much, and I offered $100 if the cards fit me on age and general description. He wanted $500 and we settled at $200. "Okay, meet me here Friday at the same time," he said, and skittered out to the street.

I met him that Friday and he had a set of cards that came close to me on description. But I wasn't quite satisfied, and he aimed to please. Before we finished dickering I had examined 18 sets—and, finally, I had myself a tailor-made fit.

My name was Jackson. I was five feet six inches tall, weighed 160, had gray eyes and wavy hair. I was 4-F in the draft for physical reasons and I had a job in a war plant. My new papers said so, and who was I to argue?

As more camouflage, I bought a round tin badge in a novelty store. It said "Inspector" and looked like the identity discs issued to some war workers. I wore this thing pinned to my shirt.

Cons in Stateville, the screws and some of my visitors often asked me later how I dodged the law on the outside. The truth is that I didn't dodge. I lived like hundreds of other men, only they were working stiffs and I was a fugitive.

I wore good enough clothes, but nothing gaudy. My hat came down well on my forehead. I wore glasses, issued to roe in prison, and the old photographs of me in the paper showed me without them. If that adds up to a disguise, I'm Mary Margaret McBride in a cell.

My new papers made it easy for me to buy a cheap used car. I drove around Chicago and out into the country through the Forest Preserves. I saw movies, dozens of them. I drank nothing more than a beer or two now and then, but a few bartenders became friendly.

Coming out of the Tivoli Theater late one afternoon, I had one of my biggest starts. Under the bright lights of the marquee, I met two ex-cons from Stateville. They whooped at me, shook my hand, clapped me on the back and wanted me to go on a celebration.

I got away from there fast. They were good guys, but one of them might take a pinch some day or get picked up for parole violating. It might be too much of a temptation for him to talk himself out of trouble by telling where Roger Touhy was.

About six weeks passed and I never saw any of the guys who went over the wall with me. The Owl was the only one who knew where I lived. One evening he came calling. With him were Stewart and Nelson, and that didn't sit well with me. I didn't want those trouble makers to know where I was.

"Thanksgiving is coming up, Rog, and we all ought to be together," Banghart said. "We got two nice apartments out near Broadway and Wilson. Come out and stay with us, at least for the holiday."

It didn't sound too bad. Living like a hermit was getting dreary. There wasn't much point in it any longer, now that Stewart and Nelson knew my address. I packed up, went with them and moved into one of the apartments with Banghart and O'Conner.

No dice. On the second night, all seven of us were drinking beer and playing cards when a rumble started. Darlak wanted to move into the apartment where I was. I said no, that it was crowded enough with three of us. I insisted on a room by myself.

Nelson was a little drunk and got mean. I tried pacifying him and Stewart, who was pretty soggy, jumped in. I gave him a slap in the mouth and left. I had the telephone number of the flat, and I told Gene and The Owl: "I'll keep in touch with you, but if you ever again tell those other three bastards where I am, I'm through with all of you."

My next stop was a room with an old lady on Wood off Madison, back near the Skid Row belt again. I had a line on her because she had a son who did time in Stateville and now was in the can in another state up north. She didn't know me from the name on my Social Security card, but she took me in when I mentioned the son.

"Terrible" Touhy still made headlines in the papers. An armored car carrying a $20,000 candy company payroll got robbed out in the suburbs, and they blamed me and my gang of "escaped terrorists" for that one. In the next edition there was a story saying I had bribed my way to South America ten days earlier. I was reported seen all over Chicago —at times, in two places simultaneously.

The FBI was making things tighter for me all the time. I learned that when I went out to suburban Des Plaines one evening to look at the house with swimming pool, where I had lived with my wife and sons so many years ago.

I was feeling sloppy sentimental and I remembered that I had an old friend, a square, in the village of Cumberland nearby. I drove over there and rang his bell. He opened the door, looked at me, winked and did an acting job that would have won laurels on Broadway. "Yes, sir?" he said, in the tone people have for door-to-door salesmen. "What can I do for you?"

I looked past him into the living room. Two young guys in bankers' gray suits and Arrow collars were sitting there with briefcases beside their chairs. FBI agents, sure as J. Edgar Hoover has jowls.

It was my cue, and I blabbered something about hearing he was in the market for a good used car. My friend said, "No, thank you," and shut the door in my face. I got out to the street and around the corner to where my car was parked.

The Federals took a couple of minutes to get the polite looks off their faces, and then took out after me. I was long gone, threading my car through alleys and side-streets, but I had learned something. The FBI was everywhere.

Another time, I pulled into a filling station at North and Damen Avenues for gas. A car was at the next pump and the driver—a city cop in uniform and wearing a gun—was standing beside it.

He came walking toward me, and I was sort of mesmerized. He didn't reach for his gun, but I was willing to give up. He leaned in the open window of my car. He grinned and I flinched. Then came the goddamnedest one-way conversation I ever heard: "Hello, Mr. Touhy. I was wondering if I'd run into you. I'd like to repay a big favor. When you were running beer, back in '29, I was in an accident and laid up in the hospital. Things were tough for my wife and kids, until you put me on your payroll. Can I help you now? Need any money?"

I couldn't speak, but I managed to shake my head. He reached out a big paw and shook my hand. The station attendant finished filling my tank, and the policeman paid him for me—which made the attendant almost as dumfounded as I was. Quite a few Chicago cops collect easy; but, they usually pay under protest I had learned years before. It was all I could do to squeak out a "thanks" to my benefactor. He told me to phone him any time I needed anything, and gave me the number of his district station. I drove away.

I sat in my room that night and wondered. If that copper had arrested me, I wouldn't have given him a bit of trouble. I didn't have a gun and I wouldn't have resisted. Pinching me would have gotten him a promotion and the award of hero cop of the year, probably. But he had remembered a favor. And I hadn't even remembered the guy, say nothing of the favor!

The time was getting close for capture. The friendly cop and those FBI men in my friend's home in Cumberland village proved that. I was covered too tight to stay on the streets for long. But what was the difference? Capture had to be sometime.

I had made my big protest against false imprisonment. My escape should get a lot of people wondering whether I really might be innocent. No longer would I be a man buried alive. After my capture, the newspapers would print my side of the story. That was the silliest hope I ever had!

When the law moved in on me, I would come out with my hands up. I would go back to prison, but I wouldn't betray the people who had helped me and I wouldn't squeal on the other six who went over the wall with me. I had telephoned Banghart a few times in their hideaway, but that didn't seem smart. Someday the FBI might be there, waiting for the phone to ring after catching or killing the others. They would trace my call and I would be next.

So, I set up a meet with Banghart—a strange meet for two of the most wanted men in America. It was St. Charles Roman Catholic Church at 12th and Cypress, where I had received my first communion.

Every Tuesday evening at six o'clock, the bell tolled in the steeple at St. Charles. It was a call to confession for people of the parish, an unusual custom for that day of the week, I guess. I would be walking up the steps as the bell started clanging.

In the church would be women with shawls over their heads. People were too poor in that neighborhood for the womenfolk to buy hats. They would be praying and going to confession in order to take communion the next day for their dead or for sons, sweethearts or husbands in the war. I had strayed away from religion a long, long time ago, but the holiness of the place still got me.

I would sit in a vacant pew. Banghart would slip in beside me and we would whisper, exchanging word on whether any of us needed help. Then we would leave, separately. If The Owl was more than five minutes late, I would leave.

Banghart, O'Connor, Darlak, Mclnerney, Nelson and Stewart were getting along okay. They hadn't committed any crimes, The Owl said. All of them were getting help from relatives or friends. They were being discreet about women and liquor. Sometimes they worked at odd jobs for walking-around money.

"I don't think they'll ever catch us," The Owl said. But I didn't agree. Pitch a needle into the biggest haystack in the world, and it'll be found if enough people look for it long enough, I told him.

The Christmas season came along and I spent hours walking on State Street, looking in the windows. Christmas is always a lonely business in prison, but it was worse for me that year on the outside. I did manage to get a message through to my wife and kids in Florida, with a few gifts. I thought of visiting them, but that would be nuts. Even if I got away with it, which was unlikely, the tear of parting would be too much.

My old landlady had me in her living room on Christmas Eve to look at her tree. It was scrawny, with the lights flickering on and off, and she was sniffling about her son in prison. I got out of there.

Almost everybody knows the gag about "lonely as a whorehouse on Christmas Eve." Well, I lived it—in a side street saloon, that is, listening to the Christmas carols on the radio and drinking beer for beer with a white-haired bartender.

The next day I went to the Empire Room in the Palmer House, got a table in a corner and ate a big dinner.

I was halfway through the meal before I began to realize that the turkey didn't taste much better than it had at Stateville. Freedom was beginning to pall on me, I guess. When I got home that evening, there was a holiday-wrapped package on my bureau. It was a necktie, a gift from the landlady. I had put a box of candy under her scrawny tree, and now she was paying off.

Every day I left my room early in the morning and took my car out of a garage on Adams Street. I would drive around or go to a movie or take long walks in the Forest Preserves. In the late afternoon, I would be back, like a working man finishing his day. The tin "inspector" badge on my shirt helped that fakery along.

And then, I felt the roof creaking, as a hunted man gets to sense. It was going to fall in on me unless I moved fast. I came home on a Tuesday afternoon and started for my room. The old lady heard me and called to me from the living room. She had three or four guests in there, having coffee and cake. I went in and she introduced me by my phony name. "This man is a friend of my son," she said. "I want him to have refreshments with us. He gave me such a nice box of chocolates for Christmas."

The lights were bright. Across the room I saw a dried-up looking guy peering at me. I knew he had me made. He was almost drooling at the chops over his fat reward in the near future. I went around the room, deadpan as Buster Keaton, shaking hands. The character I suspected had a moist, hot hand. Excitement? Anticipation? Greed for reward? Anxiety to become a hero by stooling on "Terrible" Touhy? I got the hell out of there fast, after mumbling excuses. In my room, I packed up and used a towel to wipe every surface that might hold a fingerprint. The old lady—she was probably 75—didn't deserve a harboring rap. Then, I back-doored the joint. My hunch was right, too. A Chicago copper, John Nolan, told me after my capture that a telephone stoolie had called the police, left his name, and squealed that Roger Touhy was hanging around Wood and Madison, where I had been living. He wanted a reward, the stoolie said. But I foxed him.